When Ariel Smart, a Special Education Teacher at Manhattan Star Academy (MSA), set up a monthly “period meeting” for a student and her family, Yuvania Espino was surprised but grateful. Her daughter Mia Simpson started menstruating and Espino found herself turning to Smart for guidance.

“It’s really refreshing to be able to reach out to someone...it’s hard to explain to a typical child let alone to a child with developmental disabilities,” Espino said. “I’ve been so comfortable with Ariel and other MSA staff. They take you on these journeys where typically questions like these may be a bit uncomfortable, but for them it’s like asking, ‘what’s for breakfast?’ There’s no hesitation, there’s no pause, it’s just like, ‘this is what we do to help and if we don’t have the answers, we’re going to find them.’”

Conversations around the social-sexual health of students are commonplace at MSA. That makes the school an exception among schools serving students with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD). According to a recent New York Times article, only three states explicitly include students with disabilities in their sex education requirements. Five states mandate some type of health curriculum for learners with disabilities, but what is actually taught is often left to individual schools and many times overlooks the evidence. At MSA, members of a sexuality task force, comprising more than 20 staff members, have been working with Consuelo Senior, Assistant Director of YAI Knowledge, to create a social-sexual curriculum that addresses the needs of students from preschool through their graduation at age 21.

“It’s important, especially when it comes to kids with disabilities, that we teach them that, before we touch their bodies, we tell them what we’re going to do. So that they’ll learn if somebody comes to touch their body without asking, that’s not OK,” said Senior. Since people with disabilities are seven times more likely to be victims of sexual abuse than those without disabilities, learning about body boundaries can be crucial. Senior also points out that learning social norms and laws helps ensure that people with I/DD do not unwittingly become perpetrators through behaviors they may not realize are inappropriate such as masturbating in public or sexually harassing a coworker.

Learning about consent in developmentally appropriate ways is just one piece of MSA’s curriculum, which has been in development since 2019 and is formally rolling out this fall after being piloted throughout the summer, consists of four general areas—body parts, safe touch, health, and safety and boundaries. Each area is adapted to the specific needs of each student. Resources and lesson plans are then being saved in a shared database so that teachers and therapists can access information and know what each student has already learned.

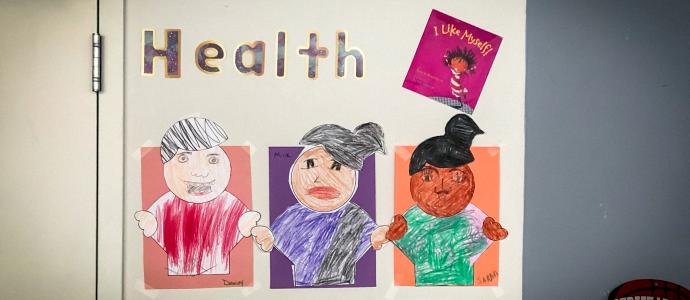

“We have a ‘don’t reinvent the wheel’ approach,” explained Smart. “We want to take what’s already out there and create programming for our students. So there’s a lot of adaptations and gathering of resources and putting it into a single program.” Smart also pointed out the importance of having a proactive curriculum, so they can address potential issues, such as the onset of puberty, before they occur. This includes preparing pre-puberty kits, discussing bodily changes, and using lots of visual aids. When children with I/DD need personal hygiene products, both Smart and Senior stress the importance of choice. Based on each child’s unique sensory issues, they might need to try a variety of deodorant styles or menstrual products before they find one that works for them. By equipping children and their families with social-sexual knowledge and tools, MSA is preparing students for life beyond the four walls of the classroom.

In addition to her monthly period meetings, Espino has already seen Simpson apply what she has learned in the real world. At a recent pediatrician’s visit, Simpson slapped the doctor’s hand away and said “no.” Although initially surprised by the reaction, both Espino and the doctor were quick to praise Simpson’s instincts. “At first, I was like, ‘oh Mia,’ but then I thought, ‘that’s so great!’” said Espino. “That comes from what she’s taught at MSA.”

For Smart, having students apply their knowledge outside of school is the main goal of the program. “When you think about social-sexual health, we’re teaching students how to navigate through the world and have bonds and relationships with other people,” she said. “It’s really an extension of social skills. It’s the missing piece that brings it all together because it focuses on caring for yourself and making sure you’re safe and that you’re a safe person.”