When young people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD) have complex mental health and behavioral needs, they can be marginalized by their own schools, forcing the burden of alternate arrangements onto families when the classroom door closes. According to a recent New York Times article, hundreds, perhaps thousands of students with I/DD all over the country are subject to informal school removals each year.

In New York State, a program called START/CSIDD works to build support across service systems to equip children aged 6 and above to thrive in homes and community institutions like schools. While the START/CSIDD abbreviation is a mouthful (Systemic, Therapeutic, Assessment Resources and Treatment/Crisis Services for Individuals with Intellectual and/or Developmental Disabilities), its objectives are not: offer crisis prevention and response services, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Stefon Smith, Regional Deputy Director of YAI START/CSIDD, has worked with many families to help get students back in classrooms with the support they need and move to eliminate what the National Disability Rights Network points out as a serious human rights violation.

“One idea behind behavioral health is that it’s not your son or daughter who needs to change, it’s that the system around them needs to understand them better and provide better support,” Smith said.

Understanding a child’s unique needs is an important piece of a complex puzzle.

START/CSIDD sees many students who get pushed out of the classroom. Karran Singh, father to Karishma, a 20-year-old Brooklynite who has received START/CSIDD services since 2018, said his daughter has struggled in school since she was a young child.

“I wish the schools were more equipped for kids like her,” Singh said. “They should have a place where kids can calm down and have a break. That would be great, instead of calling EMS. Regular teachers don’t have the patience. You’ve got to keep them calm.”

Linking families, education advocates, and school administrators, START/CSIDD opens channels of communication and provides resources as needed.

One valuable resource is a cross-systems crisis plan. Crisis plans cover early warning signs, positive psychology interventions, how to avoid triggers, and other steps to help prevent crises. Schools can also get coaching from START/CSIDD, where a therapeutic coach comes in and observes the student in the classroom, so they can make specific recommendations based on each person’s needs.

“There may be a correlation between what someone eats at lunch and an increase in distress after that,” said Smith. “It can also depend on what medications they’re on. But the schools that are open to us, and that call us for resources and call our crisis line, we do see some success there. But it takes a while to get to that point.”

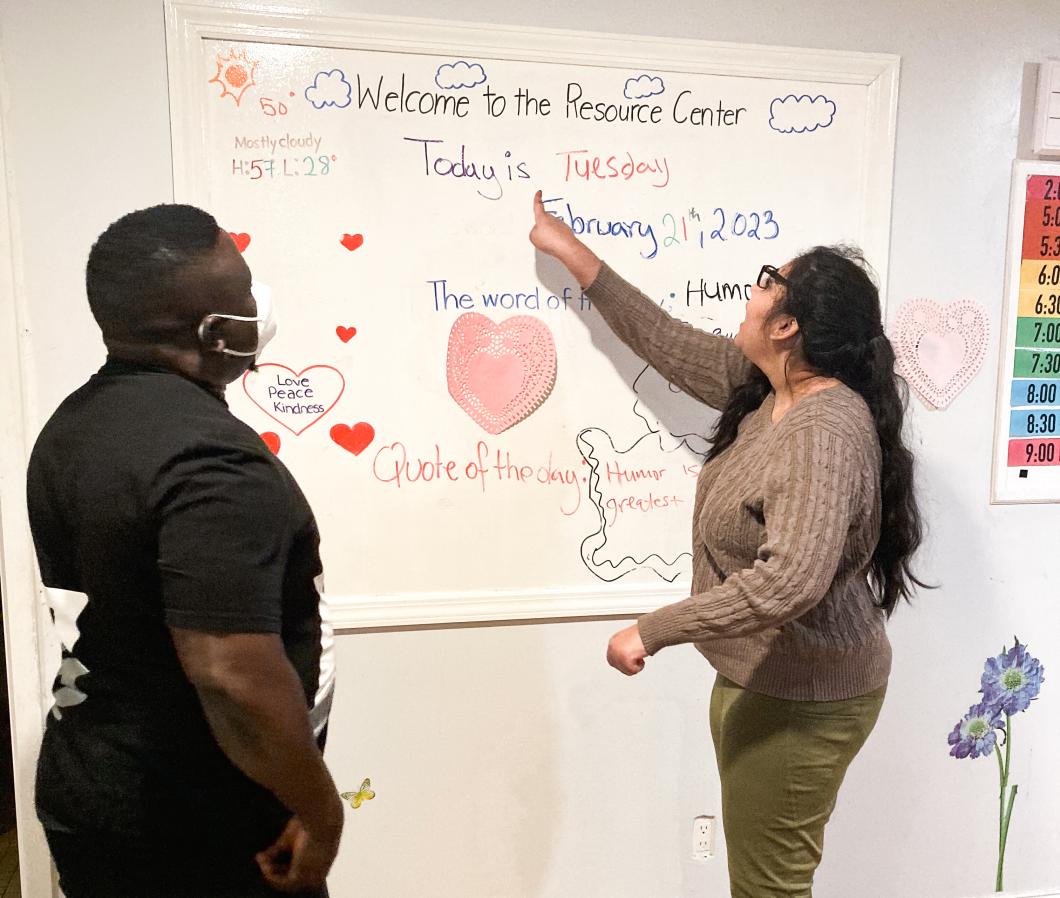

In Karishma’s case, she spent a few weeks at a START/CSIDD Resource Center so staff could identify her vulnerabilities, her early signs of distress, and how to best support her. After that initial intervention, her school became more open to collaborating.

“The system around her is supporting her more effectively,” said Smith. “She’s not in it alone, and her entire support system changed as well.”

According to Smith, one unexpected key player in the communication pipeline is the bus companies that transport students to school.

“Often, if there’s no paraprofessional on the bus, the student can’t even get to school,” said Smith. “Sometimes the paraprofessional doesn’t want to work with the person because they’re ‘too complex.’ And then you look at the route and see that often the person is on the bus for more than an hour, even if they live 20 minutes from the school. That’s way too much stimulation, way too much boredom, and way too much sitting on the bus. So we work with the paraprofessionals and the bus companies as well.”

Smith’s assessment resonates with Singh: “The biggest challenge is that Karishma doesn’t want to go back on the bus. She likes to go to school otherwise, but she gets bored on the bus.”

Although Karishma has more support today than before she started with START/CSIDD, Singh said that Karishma is currently in school three or four days a week, and she continues to be removed from the classroom.

“She needs activities. She likes going out, she likes doing things, but they need more resources at school,” Singh said.

Even with collaboration between all parties, there are no easy solutions. Smith points to limited school resources—both financially and in terms of staffing—as an ongoing challenge.

“A one size fits all approach does not work,” said Smith. “Collaboration between schools and behavior health services, such as START/CSIDD, has shown more success in limiting school removals and decreasing behavioral concerns. People need to all come together and we have to think outside the box.”