Elizabeth Annarella, YAI’s “employee of longest-standing,” is a resident expert in the history of supported employment (SEMP). She began at YAI in 1977 and has worked in residential, day, and community programs. But Annarella’s career gave her a front-row seat to observe the gradual integration of the workplace for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD).

A familiar presence at YAI, even new staff notice how Annarella combines a no-nonsense posture about supporting people with I/DD with the easy warmth of a long-time friend. By any measure, the changes over her 44-year tenure have been staggering. Consider, for example, wages. When Annarella started at YAI, minimum wage in New York State was $2.65 per hour. If that seems insignificant, compare it to earnings that came from sheltered workshops, the prevailing model of employment for people with disabilities at the time.

“In those days, paychecks could amount to three or four dollars for two weeks of work,” she said. In sheltered workshops, as many as 60 people with I/DD would spend the day on an assembly line, manufacturing pens or stuffing direct mail packets. Wages were calculated by the piece.

As a first exposure to the world of work, Annarella quickly acknowledged that sheltered workshops were an improvement over people being warehoused in large institutions. But just barely.

“When people came out of places like Willowbrook, employment was on everyone’s mind. I remember how excited everyone was to see their first paychecks. But sheltered workshops were a dead end. They didn’t offer training and people with disabilities were not part of an integrated workforce,” she said. “Separate but not equal.”

Over time, Annarella saw people transitioning to jobs where they interacted with the community.

“By the early 1990s, people who needed less support often had county jobs in parks and sanitation or in carved out positions awarded through an informal patronage system,” she said. “But they did not have job coaches and those jobs were not available to everyone, so the system, if one could call it that, left a great deal to be desired.”

In 2000, employment became a Medicaid-funded service. But even with the State-mandated phase-out of sheltered workshops, Annarella knew that people with I/DD would benefit from help to enter the competitive job market.

“When we started with employment, we were small. We had to put pressure on employers and found out what kind of positions gave people with I/DD a chance to excel. There was excitement associated with the program even then, maybe because everyone knows what it means to go to work.”

In 2014, the State’s Office for People with Developmental Disabilities (OPWDD) published its influential Transformation Agenda, a roadmap for sweeping, systemic change. The Transformation Agenda sought integration within the community, programs that reflected individuals’ needs and wants, and measurable outcomes. For employment services, this was the start of the modern age.

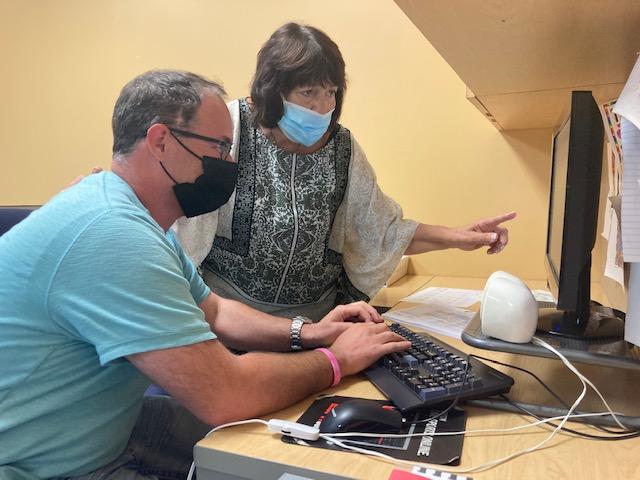

Today, YAI’s employment initiatives department supports more than 450 people in New York City and the surrounding suburbs. Services begin with assessing job readiness. People participate in trainings where they learn about the workplace and “on the job” social cues such as the difference between personal friends and work friends. Getting ready for a job search, creating a resume, and preparing for a job interview come next. When someone is hired, they are assigned a job coach who visits the workplace at regular intervals, checking in with employee and employer to make sure things are running smoothly. The longer someone is employed, the longer the interval of visits from job coaches.

Even as more employers recognize the value of hiring people with disabilities, poverty and unemployment remain persistent problems. Nationally, people with I/DD struggle to find meaningful work. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, rates of employment hover around 20 percent, a figure that has held steady since 2009.

Annarella sees opportunity in the current labor shortage because the data on supported employment are particularly compelling. Historically, people who receive support through YAI’s employment program remain on the job for an average of 7.9 years, more than three times the average tenure for neurotypical people. Employers normally report great satisfaction, citing people who are hard-working, reliable, and seldom call in sick.

“I’m hopeful about what’s ahead. We’re getting calls from FedEx and Amazon, from restaurants, all in need of help. These are national employers we’ve never heard from before,” Annarella said.

As Annarella prepares for her 45th year, she has observed a distinct shift in focus toward programs for younger people. Guided by the idea that reaching people earlier in life helps them become more successful, programs for high school students mix classroom education with internships that cultivate a range of workplace skills that can be transferred upon graduation to competitive employment.

“It’s encouraging to see this emphasis on younger people. The earlier people learn, the longer and more interesting a career they will have. People underestimate the importance of work in establishing identity. We should all fall in love with what we do. I certainly have.”