Sexual assault is one of the most traumatic, isolating experiences a person can go through. According to the National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), 94% of women who are raped experience PTSD symptoms over the two weeks following their assault. For many, these symptoms can last a lifetime or get worse with time. Pair this trauma with an intellectual or developmental disability (I/DD), and victims are routinely dismissed, overlooked, or further traumatized by the reporting process. Project Shield, a collaboration between the Brooklyn District Attorney’s office and YAI, has been working to support sexual assault victims since 2004.

Sexual assault is one of the most traumatic, isolating experiences a person can go through. According to the National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), 94% of women who are raped experience PTSD symptoms over the two weeks following their assault. For many, these symptoms can last a lifetime or get worse with time. Pair this trauma with an intellectual or developmental disability (I/DD), and victims are routinely dismissed, overlooked, or further traumatized by the reporting process. Project Shield, a collaboration between the Brooklyn District Attorney’s office and YAI, has been working to support sexual assault victims since 2004.

Project Shield takes a holistic approach toward preventing sex crimes against people with I/DD by talking to students in school, training law enforcement and medical staff in interacting with victims, and supporting victims to make informed decisions about consenting to forensic evidence collection kits. It also works with family caregivers, social services agencies, and others in order to prevent and spot signs of abuse. The program is one-of-a-kind in New York State.

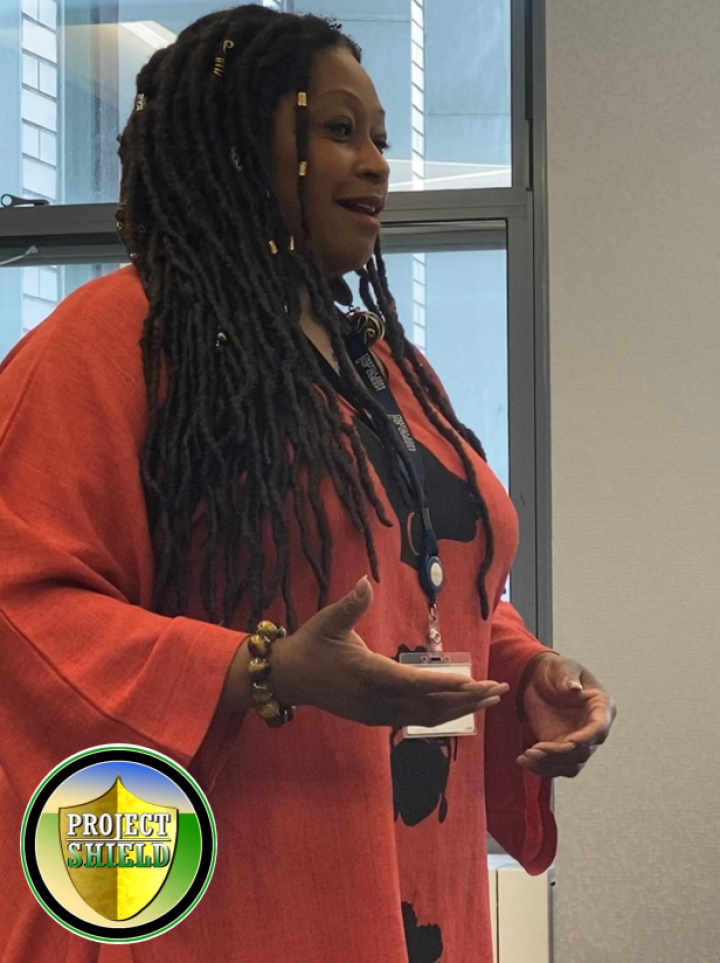

According to a 2018 NPR story, people with I/DD are seven times more likely to be sexually assaulted than people without disabilities. For Consuelo Senior, YAI’s Assistant Director of Training, Project Shield is crucial for working to reduce that frequency.

“Education is so important,” said Senior. “People with I/DD are misunderstood and not understood. Project Shield helps to give a voice to people who often don’t have one in society. We’re also teaching community members how to interact with people with disabilities so they won’t become victims.”

Within Project Shield, YAI acts as the Brooklyn DA’s education partner—creating course materials, performing sexual consent evaluations, and co-leading training sessions. Every year, Project Shield trains roughly 1,200 people from a range of professional backgrounds. In the training for law enforcement officials, the focus is on learning how to interact with people with disabilities.

“We debunk myths, specifically, sexual myths,” said Senior. “And we give tips on communication. Even if someone has a support staff with them, you look at the person and address the questions to them. Someone who’s rocking isn’t getting ready to hit you. Maybe they’re nervous. Maybe they’re too cold or too hot. We also give tips on how to ask open-ended questions."

Margarita Khanina, the Project Shield Coordinator who co-facilitates the trainings for medical professionals, emphasizes that helping doctors and nurses learn about consent for people with I/DD is vital for supporting victims.

“We always get questions about what encompasses a sexual consent determination,” said Khanina. “The other thing that always comes up is the forensic evidence collection kit. That specific exam is not a medically necessary procedure. It is something that is done to collect evidence for a potential criminal case. So there are always questions around consenting to that exam and what that looks like.”

Whether a victim ultimately consents to an exam or not, Khanina says that a person who’s been specially trained to work with people with disabilities can make a huge difference.

“Having someone in their corner as early as possible is even more important than for someone without a disability who has a criminal case,” said Khanina. “Because people with disabilities really do face more barriers. And usually when they’re telling somebody it’s not the first time something bad has happened. Regardless of whether or not we are able to have a prosecution in their case, the validation in itself can really help somebody in the future figuring out what to do, and help them process how to respond.”

In addition to the importance of supporting and empowering victims, Project Shield’s work addresses many of the nuances that slip through the cracks in other jurisdictions.

“There are domestic violence cases where people have undocumented intellectual disabilities,” Senior said. “And even if someone doesn’t know it’s abuse, that doesn’t mean it’s not abuse. Your ‘yes’ could not be an informed yes. And if someone is found to be not consenting, they cannot testify in front of a jury. So then the evidence needs to be even more solid.”

“I’m hoping this will spark people to go to their own communities and request a program like this,” said Senior.

To learn more about Project Shield and unique trainings offered by YAI, please contact yaiknowledge@yai.org